Not only do poor blasting practices erode mines’ financial bottom lines – they are also bad for the environment, according the BME technical director Tony Rorke.

Highlighting that a number of greenhouse gases are generated in the explosives chain, Rorke said that nitrous oxide (N2O) is particularly dangerous – being almost 300 times more harmful to the climate system than carbon dioxide.

“Ironically, there is little public awareness of N2O, which is why it is sometimes referred to as the ‘forgotten’ greenhouse gas,” he said. “Containing N2O emissions can also present an opportunity to mines and other explosives users to significantly improve their carbon footprint.”

As a leading supplier of emulsion explosives, Omnia Group company BME is concerned about ensuring production process and the application of BME products is environmentally-friendly.

“Sourcing our nitric acid and ammonium nitrate from Omnia, our product benefits from the fact that Omnia’s two Envinox plants scrub 98% of the N2O from the production facility’s absorption tower – ensuring that our customers’ sustainability reporting is not unduly compromised,” said Rorke. “But there are more environmental benefits at operational level that can be achieved with good quality blasting, which will reduce the amount of greenhouse gases emitted.”

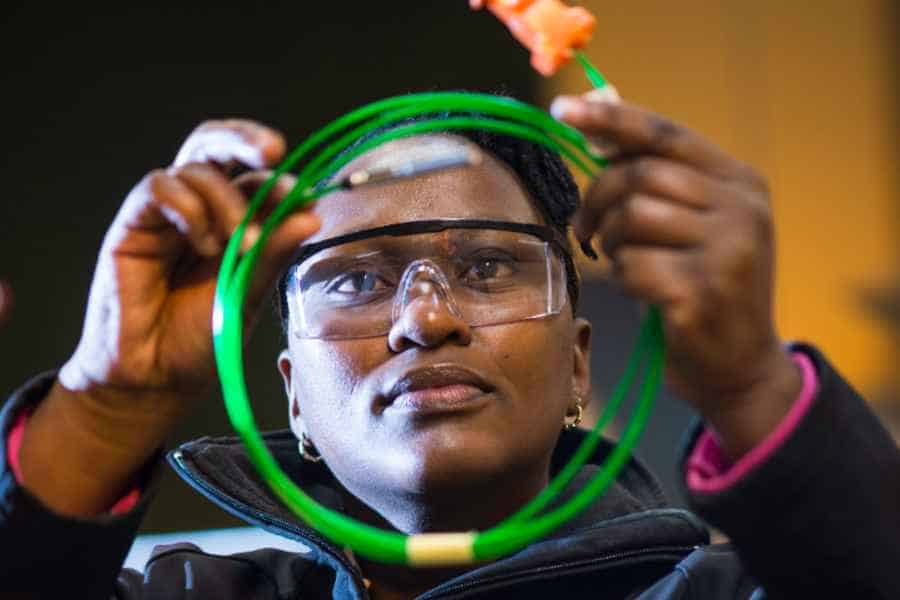

One challenge is to reduce the amount of nitrous oxides produced during blasting; evidence of nitrous oxides being generated by a blast is usually the orange smoke cloud that rises after detonation.

“This can be caused by water in the ground or by poor blast timing,” he said. “It can also result from blasters not taking into account the nature of the rock and how this could damage explosives – causing them not to react properly.”

A poor blast design or timing design is likely to result in a bad blast, where not all the explosive is fully detonated; under these conditions, nitrous oxide fumes will be produced – with severe consequences for the environment.

He emphasises that there are other downstream activities on a mine that also contribute to the operation’s carbon footprint – and which can also be improved to result in less CO2 emissions. Research shows that for every cubic metre of rock mined, about 4 kg of CO2 is produced by the explosives, 5 kg of CO2 by the process of loading and hauling, and 27 kg of CO2 by crushing and milling – a total of some 36 kg.

“An important negative result of a bad blast is difficult digging conditions – loaders will struggle to dig where the required fragmentation has not been achieved, for instance,” he said. “This means the machines will burn more diesel and emit more CO2.”

Coarser fragmentation will also lead to less efficient functioning of the crushers and the mill, which will in turn consume more electricity – also a major greenhouse gas contributor.

“By blasting badly, a mine will also effectively be losing ore; so despite creating all these extra greenhouse gases, there is even less ore to show for it,” said Rorke. “The result is that more mining is necessary to reach the targeted production levels.”

He said there is plenty of scope, therefore, for mines to reduce their carbon footprint by improving their blasting performance.

“It has been shown that throw blasting can cut greenhouse gas emissions by 1-2%, and improved fragmentation can achieve even larger reductions of about 6%,” he said. “Even greater potential lies in reducing ore losses, with efficient ore-waste separation capable of reducing greenhouse gas output by between 5% and 25%.”

As mining companies are required to report more thoroughly and systematically on their triple-bottom line – including the environmental impact – they should pay greater attention to their blasting practices, said Rorke; they may find they are pleasantly surprised by what can be achieved in terms of both reducing greenhouse gases and improving mining efficiencies.